The Topography of the Lungs is one of the crucial early documents of European free improvisation. Recorded in July 1970, this lively, inventive trio record introduced a decade in which European free jazz would increasingly splinter from its American progenitors, developing a new branch with fewer overt roots in the jazz lineage. The album brings together British improvisers Evan Parker and Derek Bailey with Dutch drummer Han Bennink, cross-fertilizing between two of the most prominent national scenes that were pushing towards this attitudinal and aesthetic change in the late ’60s.

The Topography of the Lungs is one of the crucial early documents of European free improvisation. Recorded in July 1970, this lively, inventive trio record introduced a decade in which European free jazz would increasingly splinter from its American progenitors, developing a new branch with fewer overt roots in the jazz lineage. The album brings together British improvisers Evan Parker and Derek Bailey with Dutch drummer Han Bennink, cross-fertilizing between two of the most prominent national scenes that were pushing towards this attitudinal and aesthetic change in the late ’60s.

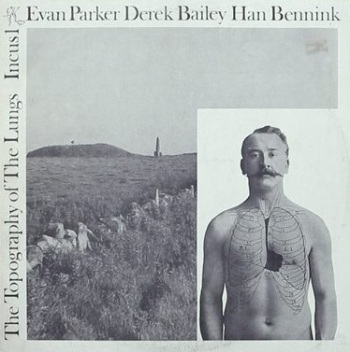

It is a particularly important record for Parker and Bailey, as the first album released under their own names rather than as members of someone else’s group. (Parker has since retroactively tried to claim sole leadership of the date on reissues, an odd throwback to jazz orthodoxy from a musician who should know better; there’s no real “leader” in the traditional sense on this truly collaborative effort.) After debuting on the Spontaneous Music Ensemble’s Karyobin, Bailey and Parker appeared in 1968-1969 on albums by musicians like British drummer Tony Oxley and German saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, developing their nascent voices further. Topography was the first release on the musician-run Incus label, founded by Bailey, Parker, Oxley, and the journalist Michael Walters. Incus, unsurprisingly given those involved, would be a key chronicler of the British improv scene in ensuing decades, placing both aesthetic and business decisions in the hands of the musicians involved.

Bennink was more established prior to this session: he’d played with Eric Dolphy in 1964, shortly before the legendary saxophonist’s death, and with Willem Breuker and Misha Mengelberg had founded the Instant Composers Pool in 1967. The ICP and the confluence of musicians who contributed to the loose collective’s performances and records made the Netherlands one of the centers of forward-thinking European jazz and improvisation by the end of the ’60s. The Dutch scene, driven by players like Bennink and frequent outside collaborators like Brötzmann, developed an intense, noisy response to the ’60s “energy music” strain of free jazz, while British improv often ventured into more abstract, introspective terrain. The two sensibilities intersect here, as they often would over the next few decades, and the tension between them creates much of the album’s edge.

The album opens with the side-long “Titan Moon,” introduced by Bennink’s irregular drumming, creating a stuttered arhythmia that’s just off enough to avoid suggesting a steady beat. Each hit is forceful, nearly violent. Bennink is an unrelentingly physical drummer: even without seeing him in action, it’s easy to imagine him lunging at his kit, putting his full weight behind each blow, all while assembling a bevy of clicks, clatters, and crackling percussive minutiae around the heavier beats. Bailey and Parker weave between Bennick’s hits at first, with tentative shards of guitar feedback and abrupt sax phrases that seem to dart out into the drums’ path and then retreat, like a skittish animal afraid of being crushed underfoot.

The trio soon converge in a frenzied blowing session, the wild energy of which briefly recalls ’60s free jazz, everyone playing over one another at their loudest and most enthusiastic. It’s just a momentary touchstone here, though, as the music quickly shifts and fractures yet again, all this occurring within the first few minutes of the piece. The pace is frenetic, with all three players displaying a responsiveness and agility of thinking that prevents them from settling into familiar ruts.

Before six minutes have even passed, Bennink lays out for just long enough to let things settle down and spread out a bit, introducing a sustained segment in which the group explores more spacious, dynamic territory. The three players drop in and out in rapid succession, allowing for different combinations of solos and duos within the group. Bailey solos for a stretch, with Bennink occasionally contributing percussive clangs and scrapes that nicely offset the finicky guitar clusters, then Bennink plays on his own, and soon Parker joins in on tenor sax, dueting with sculpted feedback from Bailey. Bailey’s playing already displays much of what would make the guitarist so special: the distinctive tight, insular language of his music, the way he crafts these incredibly fast abstractions that suggest incredible virtuosity but somehow avoid the conventional signifiers of virtuoso guitar wankery.

Parker is extraordinarily attuned to his frequent collaborator’s playing, as well. There’s a stretch towards the end of “Titan Moon” where Parker seems to be echoing the phrasing of the guitar, matching Bailey’s ceaseless chains of notes with a series of squeaky high sax tones, similarly chopped and abrupt. The effect is striking, at times seeming like a bit of gentle prodding – soon after, Bailey shakes things up by producing a sheet of droning feedback against which he sets some harsh scraping noises – and at other times seeming like a conversation between two friends whose languages and ideas on their respective instruments had developed in tandem over the preceding years.

Bennink is thus the obvious outsider here, though he hardly seems out of place. He adds tremendously to the music’s density and sense of excitement, never letting the other two musicians rest or get too comfortable. When things threaten to topple completely into anarchy, Bennink’s willing to sit back and let some space back in, but conversely, he’s even more eager to unsettle the quieter moments with sudden outbursts, or to introduce some rambunctious humor by howling or moaning into resonant containers. Bennink seemingly has a huge array of instruments at hand, and he is constantly introducing new tonal colors and textures into the mix: metal drums, bits of percussive junk, cymbals, bells, and so on. Just trying to follow what he’s doing from moment to moment can be a (very rewarding) challenge, and at times he seems to have more limbs than is humanly possible, producing so many sounds at once that one wonders how he manages to hit all those different surfaces simultaneously.

On the B-side’s “For Peter B & Peter K,” appropriately dedicated to Bennink’s German colleagues Brötzmann and Kowald, Bennink takes center stage with a barrage of rolling, pulsing drums. It’s a worthy showcase for Bennink’s percussive inventiveness, but it pushes Bailey and Parker to the sidelines for much of the piece’s brief length, betraying the group interactivity that otherwise dominates on this set. This kind of showy virtuosity seems out of place in this context in a way that it wouldn’t have in the free jazz from which this music had only recently branched. Even so, beyond Bennink’s joyful showboating, there’s some interest at the fringes too, as Bailey quietly plays in a more tonal, almost plaintive way than usual, tossing some delicate semi-melodic figures at the churning waves of Bennink’s drum assault.

On “Fixed Elsewhere,” Bailey drops more into the background, playing in a low-key rhythmic style that gets mostly drowned out by what otherwise sounds like a drums/sax duo. Again, the lack of balance drains much of the interest from the trio’s aesthetic; on “Titan Moon,” they’d seamlessly managed dynamics and exchanges, keeping the texture fresh from moment to moment instead of developing the mostly static structures that dominate these two shorter tracks. “Titan Moon” is an early ideal of free improvisation, evincing a state of intuitive communication and fluid interplay to which all three players contribute equally; the B-side’s first ten minutes suggest the difficulty of attaining that kind of balance consistently.

The remainder of the B-side is taken up by the 12-minute “Dogmeat,” which is another superb demonstration of the trio’s talents, although without repeating the formula or style of “Titan Moon.” This piece is spikier, a roiling and uneasy sea that might be calm and settled one moment, explosively heaving the next. There are stretches of near-silence, broken by buzzy vibrations and percussive rattles from Bennink, bits of feedback from Bailey, or isolated Parker tenor squeaks. At other times, the music seethes and shakes, the three instrumentalists careening off one another with ferocious energy.

Parker provides the most obvious linkage back to jazz, throughout the album but especially here, his playing often sounding a lot like free jazz soloing that’s merely been ripped from its original context. The saxophone, particularly the tenor that Parker mostly sticks to here, would prove one of the most stubborn instruments in attempting to shake off that lineage, retaining strong connections to the jazz vocabulary even in contexts where those associations were being subverted. The sense of space and dynamics comes much more from Bailey and Bennink, who switch unpredictably between explosiveness and restraint. Certainly, this is Bailey’s most fascinating performance on the record, as he encompasses melancholy melodicism, noisy feedback-sculpting, and the kind of finger-shredding intricacy for which he’s best known.

Towards the end of this piece, things come together unexpectedly after the record’s quietest, tensest segment, a few minutes of near-silence continually interrupted with spiky interjections. Finally, the hush breaks with a surprising burst of fuzzy tonal guitar from Bailey, soon joined by Parker, playing a yearning post-Coltrane tenor melody, while Bennink stomps away with the album’s most regular, steady beat, syncopated and even funky in an off-kilter way. It’s effective because it’s so startling in this context, these three improvisers suddenly cohering, seemingly spontaneously, into a ramshackle approximation of late ’60s spiritual free jazz.

As cathartic as this feels, it’s also a pretty odd way to end the album, since for much of the rest of its length, Topography is a determinedly post-jazz recording, pushing the language of improvisation further and further beyond the parameters of jazz. There are still nods here and there on the other tracks, but by this point, these three musicians had developed an abstract, original approach that’s already fairly distant from Parker and Bailey’s recorded debuts, just two years earlier, on the SME’s Karyobin. On the two longer tracks, especially, the trio attains an intuitive improvisational balance that allows them to explore a substantial amount of territory in terms of dynamics and textures. The Topography of the Lungs is another important early step in the careers of three of European improv’s biggest players, and thus a piece of free improv history. Only fitfully is it more than that, a satisfying recording in its own right, but when it all comes together it is quite great even beyond its significance.